The project management literature we discuss during the course often addresses issues related to uncertainty. Graham Winch conceives the building process as a “progressive reduction of uncertainty through time”. During construction, we are confronted with day-to-day issues and uncertainties but also long-term uncertainties. Often, we have multiple issues, and these issues make managers, responsible for the budget, nervous because change often comes with extra costs and many changes come with high costs. We can divide the issues around uncertainty into categories. The more technical-related things and the more human-related issues. Solving issues is a matter of “performance” or “taking a position”. Do I take a formal stand or a relational stand?

The formal stance is contractual. Then you try to relate the arising issues to the contract, the procedures, and the formal requirements. Is the issue mentioned somewhere in the contract yes, or no? Did the contractor follow the formal procedure? Is the proposal in line with the building specifications? Is the contractor entitled to ask for a change order or is it somewhere covered in the contractual agreements? Is the offer acceptable or is the offer too high? Is the contractor able to prove the validity of the change in a legal sense and entitled to extra payments?

When talking about human issues that cause uncertainties you can think about distrust, information asymmetry, moral hazard, strategic misrepresentation, optimism bias, dysfunctional conflicts, the management of interpersonal relationships, understanding project ecology, organizational culture, climate and demographics, expectations, intuition and judgment, biases, power conflicts, trust, and learning (Monteiro 2015). We can solve human issues through teamwork, team building, leadership, and our management style.

Some years ago, I was the manager of the refit of the former ABN-AMRO bank into the Municipal Archives. It turned out that the written contract and the building specifications did not cover reality. During construction, we discovered multiple flaws in the specifications and multiple deviations from the drawings in the building.

I discussed the case of The Bazel shorty during the introduction and I explained how things went wrong. Besides the flaws in the contract and the building specifications, many of the problems were related to human relations, distrust, moral hazard, conflict, and performance.

After the tender at the start of the project, both, the contractor, and the client wanted to make the project a success. The intentions were positive. The contractor was eager to start and work. A prestigious building that would be good for their portfolio.

Soon, after a couple of months, things started to go wrong. Gradually the relationship between the team of the contractor and the team of the client went sour and distrust, misunderstandings, miscommunication, and conflicts seeped into the project. Despite multiple efforts to improve the atmosphere between the client and the contractor, the conflict took more than two years and ended in court.

You can imagine that both teams, the team of the contractor and the team of the client were relieved that the project was finished at last, after a long time of stress and trouble.

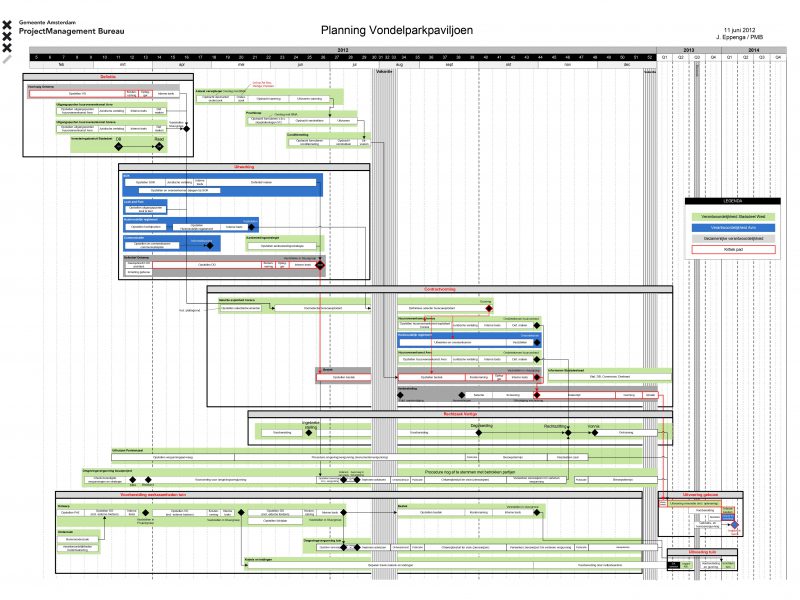

Some years later, I worked on a new project: the Vondelpark Pavilion. Out of a pre-tender procedure, five contractors were selected to deliver a price.

Surprise! One of the contractors was the contractor of the Bazel. Next surprise! They delivered the best plan and did the lowest bid.

Before we could officially award the project to the contractor, the director of the firm and I met at our office. We discussed how to proceed together and for the moment to forget the past. What we needed to do was to organize a good work atmosphere for the construction that was ahead of us. The solutions that came up turned out to be simple and workable. We agreed to meet every week to discuss progress. We agreed to call if we heard “strange things” from the building site or from team members and we agreed to organize a strict and quick procedure for additional work and change orders. We also organized a couple of informal meetings with both teams and the workers while offering them good coffee and cake.

The contractor organized the building process in a lean way and involved his subcontractors in the process. They started every Monday with a planning session to align work and to discuss the week’s challenges and possible constraints. We sometimes visited the sessions to hear what was going on.

The project went very well despite the setbacks and problems you normally have to deal with. Both teams acted professionally while solving constraints together. As a result, trust and mutual understanding grew week over week between the project teams. The same goes for the director of the contractor and me.

I have never had a better contractor!