The theme of this week is “the balancing act”.

The theme of this week is “the balancing act”.

Several papers you read this week are about seemingly opposing things. The article “From Firefighter to Firefighter” by Barber and Warn puts reactive against proactive behavior. The Chapter of Winch, managing construction projects consummately tries to bring all kinds of opposing things together. Winch puts construction as artifacts against construction as assets; he sets project integrity to process integrity. The paper by Koppenjan et al. distinguishes different management approaches: predict & control versus prepare & commit. Interestingly, they bring the two also together by stating that the approaches are “seemingly opposing”.

Winch states that the central tenet of his book is that construction project management is “a problem of management of uncertainty through time”. The solution to this problem is using a variety of seemingly opposing “tools”. To be successful as a manager and to be able to steer a project to a conclusion a large variety of skills, methods, approaches, strategies, attitudes, and performance are at your disposal and will be needed…… and they change through time as the project moves forward.

For me, managing is taking a position on the scale between proactive and reactive, between being strict and flexible, between predict & control and prepare & commit, between contract and the people, between anger and joy, between directive and cooperative, between wearing a suit or wearing jeans and sneakers.

Let me give an example.

Some years ago, I worked as a manager for the refit of the monumental Vondelpark Pavilion; The case of this year’s course. The building used to be the Dutch Film Museum for years and needed a thorough refit when the museum left to move to the EYE building in the North of Amsterdam. The owner of the building, the city of Amsterdam found new tenants, a broadcasting corporation; AVRO, and a grand café-restaurant. My team needed to take care of all user requirements which are comprehensive for broadcasting studios, internet studios, and a large restaurant with all the equipment and technical stuff. In the meantime, we needed to take the monumental status of the building into account.

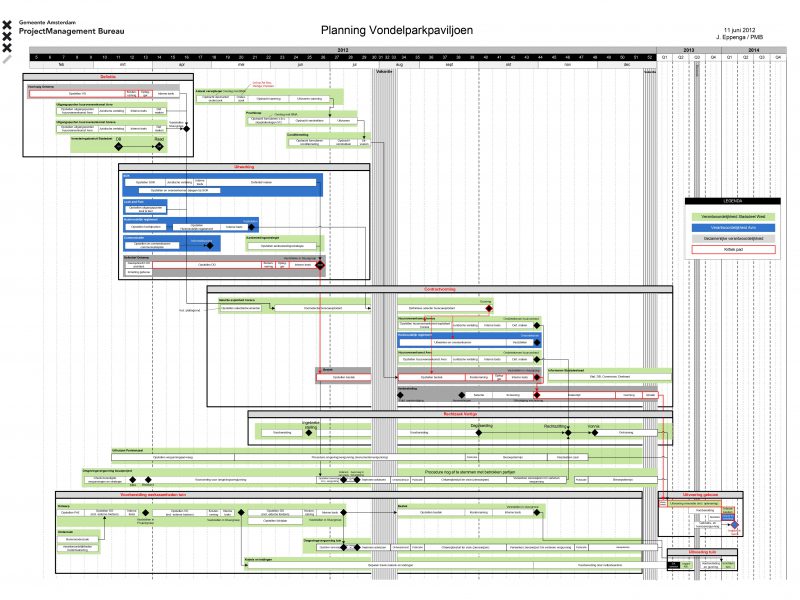

When I started the project, I thought this was just a straightforward restoration and refit job. The reason I started to compose a design team and value the work in a kind of technical and transactional way. One of the things we made was a schedule. The client, the Alderman of the city district, did not want to rush things. He wanted a solid project structure and wanted us to take care of the quality of the monument and also diminish risks, especially related to budget and time. A realistic timeline and carefulness were important. The client stated that if the schedule was realistic the chances of delay are lower than with an overly optimistic schedule. The project would take about two and half years to design, construct and complete. For the owner, the project was partly an asset to rent out. The Alderman also wanted a smooth process because he had bad experiences with another project with public and political indignation about budget overruns and delays.

That was an error of judgment related to the tenant. For the future tenants, the physical building (the asset) was a secondary thing. For them, the building was the place to be, their stage, with a highly symbolic and in-use value. Not to make money but to perform. An artifact. They wanted to open as soon as possible. Speed was everything. The prime concern of the director was to have excellent broadcasting public studios for television, radio, and the Internet as soon as possible. It became clear that the AVRO, existing for almost 75 years, wanted to celebrate its anniversary in the new building. That was, given the complexity of the refit and the time available impossible.

A week after my official assignment, I met the director of the AVRO and members of the board and we ended the meeting with a disagreement. The schedule destroyed their dream of a great anniversary in the Vondelparkpavilion. The director was so angry that she phoned the Alderman to complain about my inflexible stand and she demanded to speed up.

Immediately I understood that the project, or at least part of the project, was not technical at all, and trying to convince the director by explaining the schedule and the task complexity would only make things worse. The project was a big personal thing and of highly symbolic value for the user. I needed to change my approach completely. Instead of organizing a “technical thing” I needed to design a plan of collaboration, of mutual sensemaking, and approach the tenant in a transformational way. I needed to gain trust, and I needed to find solutions to solve this incompatible situation of speed versus complexity. I was in an uncomfortable position and I needed to solve that.

My solution was twofold and the process was a balancing act. I assigned and contracted a design team to speed up the process and move forward with the preparations for the refit. In the meantime, I dedicated most of my energy to the dialogue with the new tenants. The tenant hired a lawyer and a management consultant firm intending to force me to speed up delivery. In the following months, it also became clear to the consultant that it was impossible to deliver the project in one year. Especially because we had to deal with a state monument in the city center and it turned out the tenant had extra requirements to incorporate in the design. They understood that my schedule was realistic and we informed the director. She trusted her consultants and changed the anniversary plans.

Now I needed to deliver according to the proposed plans. The focus of the design team was to follow the schedule as well as possible, and in the meantime to solve the design challenge to fit the broadcasting stuff in the monument. I needed this to gain a little trust and to show I was in control, honoring my promises, and serving the needs of the tenant as well as the needs of the city. I needed to steer this process proactively.

Building a good relationship with the tenant was about “Prepare and Commit” and I needed to be open and clear. The approach for this part of the project was also proactive and doing it all on time because I needed conformity before I could contract a builder.

In the end, the project was delivered after almost two years. And that was faster than promised. We had multiple constraints along the way, complaining and protesting neighbors, challenges with the condition of the building, several discussions with the historic department, and many difficulties with the integration of the broadcasting equipment in the monument.

After delivery, it took the tenant several months to test and try-outs before the first broadcasts.

Luckily, I had a good contractor.

Barber and Warn (2005). Leadership in project management: from firefighter to firelighter.

Koppenjan, J., Veeneman, W., van der Voort, H., ten Heuvelhof, E., & Leijten, M. (2011). Competing management approaches in large engineering projects: The Dutch RandstadRail project. International journal of project management, 29(6), 740-750.

Walker, D. H. (2015). Playing the Project Manager. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 8(2), 393-400.

Winch, G. M. (2010). Conclusions: Managing Construction Projects Consummately. In: Managing Construction Projects; An Information Processing Approach. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons